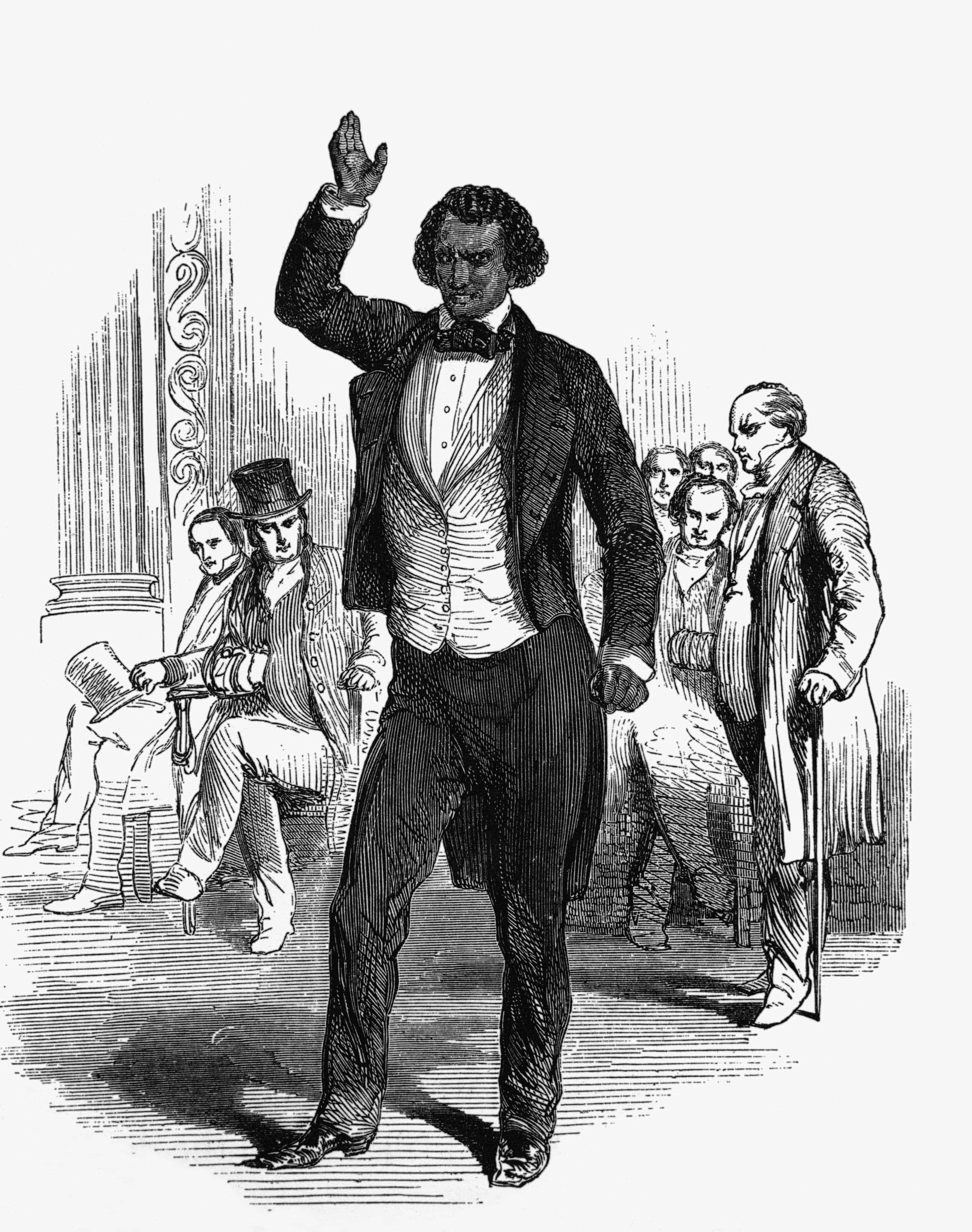

On Dec. 28, 1885 at the age of 67, Frederick Douglas gave a speech in Maryland just a few miles south of the Mason-Dixon Line that had separated slave states from free states before the Civil War. He titled his talk “The Self-Made Man.”

Douglas had more than earned the right to call himself one.

Born in 1818 on a plantation in Maryland, Douglas was separated from his family as a child. He spent much of his childhood teaching himself to read and write in secret, and it was that early self-driven education that unlocked the door to his accomplishments years later.

But like all great self-made men and women, Douglas didn’t just unlock that door for himself. He didn’t walk through and close it behind him. Instead, he dedicated his life to equality and human rights for all, working as a preacher and an abolitionist and, later in life, advocating for women and their right to vote. As he said in a lecture he gave in 1855:

I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.-Frederick Douglas

A mission that he developed for himself, having grown up in a world that was united in doing very much the opposite.

Born into Slavery

The exact day and month of Frederick Douglas’ birth is unknown. But what is known, is that he was separated from his mother, who was a slave, as a baby and that his white father was likely his mother’s owner. His earliest years were spent on a Maryland plantation with his grandmother, where he lived until he was about 7 or 8 years old.

At that age, Douglas was sent to live as a house servant with the family of Hugh Auld in Baltimore. There, Douglas experienced the first bit of what he would call providence, when the slave owner’s wife began teaching him to read. But that providence would be short-lived. The master believed that knowledge would give the young boy a desire for freedom and put an end to his wife’s lessons.

But it was too late to snuff the light that had been lit in Douglas, who continued to educate himself in secret. He realized that what his slave owner had believed was indeed true: Knowledge did lead to a thirst for freedom. And, once he knew that to be true, it is not the kind of thing he could ever ignore.

Becoming a Man

At the age of 16, Douglas was sent back to the Maryland plantation where he was born and put to work as a field hand. There, he began weekly Sunday school classes for the other slaves, teaching them to read the New Testament of the Bible. The lessons attracted some 40 or so slaves from nearby farms.

But like his early lessons in reading came to an end, Douglas’ lessons were soon stopped by slave owners. None wanted their enslaved workers becoming literate, so Douglas was moved to the farm of Edward Covey, a man with a reputation as a “slave breaker.” There, Douglas was whipped so often that his wounds never had time to heal. In his autobiography, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave,” Douglass recalls this time in his life as transformative:

You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man.-Frederick Douglas

Escaping to a New World

On Sept. 3, 1838, Douglas escaped from Covey’s farm. He disguised himself as a sailor and boarded a northbound train, where he eventually made it to the safe house of noted abolitionist David Ruggles in New York City. Suddenly, in less than 24 hours since he escaped his slave owners, Douglas was in an entirely new world. He would later write of his arrival in New York City as:

I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life.-Frederick Douglas

Just 12 days later, Douglas married Anna Murray, a free black woman he had met in Baltimore one year before. The couple moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, a town full of former slaves, and got to work.

Man with a Mission

After the hardships he’d endured, it would have been more than understandable if Douglas had chosen to live the rest of his years quietly. To enjoy his freedom in peace. But that’s not the kind of man Douglas was.

The spirit that inspired him to teach other slaves to read, and to educate himself before that, drove him to spend the next 50 years preaching the gospel of human rights and freedom. At first it was just one time, where Douglas sharing his story at abolitionist meetings. But before long, he became a noted anti-slavery lecturer renowned for his oratory skills.

But Douglas still lived in a world determined to silence him as his slave owners had tried to do. There were angry mobs who chased him, people who questioned him, and plenty who did not share his beliefs. And he was rightly afraid of being recaptured and returned to the South. But all of that struggle was far better than the alternative, to Douglas, and so he pressed on.

Rewriting the Story of Slavery

In 1845, Douglas published “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.” It became a best-seller and was translated into several languages. The book was so well-written that some people at the time doubted it could have been written by a former slave. Among its most famous passages is this phrase that Douglas wrote:

I prayed for freedom for twenty years, but received no answer until I prayed with my legs.-Frederick Douglas

A reminder that while Douglas was a great thinker and speaker, he was also a man determined to stand up and take action for the things he believed in. Which included helping others who he saw as being oppressed.

Supporting Women's Rights

At the 1848 Seneca Falls Conventions, Douglas was the only African American in attendance.The gathering was a group of activists who came together to fight for women’s rights in New York, and Douglas used his powerful oratory to argue in support of the cause:

In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.-Frederick Douglas

Douglas spoke these words in spite of the fact that it would take more than 20 years for he himself to get the right to vote. And it would take until 25 years after Douglas died in 1895, before women would get the right to vote. None of these changes came easily, but that’s not something that ever stopped Douglas from fighting for them.

Losing Support for Lincoln

Up through the Civil War, Douglas was a vocal supporter of President Lincoln, but then a key event changed his opinion. When Lincoln signed The Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, it was what so many slaves had been waiting for. It declared that all enslaved people in the states currently engaged in rebellion against the Union, “Shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

But The Emancipation Proclamation did not do something Douglas saw as crucial: it did not grant former slaves the right to vote. To a man who had been taken from his mother, who had learned to read, who had been beaten, who had escaped, who had fought for others, it was not enough for slaves to be “emancipated.” Douglas wanted to have his say. He wanted to vote.

In later years, it is said that Lincoln and Douglas reconciled, and Douglas was asked to speak at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C. in 1876. But during the Civil War, when half of a country was fighting to the death to own black people, Douglas was determined to fight just as hard for what he knew was right.

Fighting Until His Last Breath

Douglas would continue speaking and advocating for African American and women’s rights his entire life. After his first wife died in 1882, Douglas took another bold step toward equality and married a white activist named Helen Pitts,—a move that drew criticism from many, including both Pitts’ family and his own.

In spite of it all, they lived a peaceful life together at Cedar Hill, a stately hilltop home in Washington where they received visitors and Douglas played croquet with college students he mentored.

But Douglas never saw peace as the same thing as contentment. When there was still discrimination against people like himself; when people like his wife still could not vote, how could he be content? Was Thomas Edison done after his first experiment? Was Andrew Carnegie content to make his first million? Content to give his first million away? Did Abraham Lincoln stop after he lost his first election? No. The self-made never stop striving.

Douglas died on Feb. 20, 1885. Born unnoticed and into slavery, he never knew the exact day he came into this world, but his death would be marked by millions. His death was fitting: he had just returned home from a women’s suffrage meeting where he had sat next to Susan B. Anthony, when he had a heart attack and passed away.Douglas was a man who kept fighting to his very end.

Freedom Above All

But, while Douglas is gone, his place in history is secure. His 1,200-page autobiography has been called “one of the most impressive performances of memoir in the nation’s history." And his unqualified definition of freedom is a call to action even today, to oppose injustice and pursue true equality in every corner of the world. Because once the vision of freedom is ignited in someone, it will continue to burn for their entire lives.

As Douglas wrote:

Freedom now appeared, to disappear no more forever. It was heard in every sound and seen in every thing. It was very present to torment me with a sense of my wretched condition. I saw nothing without seeing it, I heard nothing without hearing it, and felt nothing without feeling it. It looked from every star, it smiled in every calm, breathed in every wind, and moved in every storm.-Frederick Douglas